Do we need a second web?

This is part serious proposal, part frustrated rant.

I’ve been watching the TV adaptation of Isaac Asimov’s Foundation lately and one thing stuck with me: the first Foundation was created with the highest ideals, but it couldn’t live up to them. The solution? A Second Foundation, built to do what the first could not.

When I look at our online world today, I can’t help but ask: do we need a second Web?

I present this as a straw man, a provocation. I have a fistful of critical responses already in my head - all the reasons why a second web is a bad idea.

But hear me out, because there is no denying that the web today is terrible.

Thirty years ago, the World Wide Web was a small research project that outgrew the lab and became a global phenomenon. Its ideals were simple but profound: information available everywhere, to everyone, and instant connections across the globe.

For a while, that vision held and the web came to define and shape our world. But by the mid-2000s, the cracks were obvious. First came the walled gardens of social networks, which pulled users into closed ecosystems. Then came paywalls, a necessity to sustain quality journalism driven by the collapse of the traditional economics of publishing. The open web began to close.

Today, much of what we consume flows through platforms like YouTube, LinkedIn, TikTok, and Substack: ecosystems that are half-open, half-closed, and designed above all to capture value from users. High-quality publishing increasingly sits behind paywalls High-quality publishing increasingly sits behind paywalls, while what remains open is riddled with clickbait and relentless data extraction.

It’s not all bleak: excellent open information still thrives on Wikipedia, arXiv, blogs, open source code, media, and archives. But the direction is clear: the open web is shrinking, and shrinking fast.

Maybe that’s fine. Maybe the idea of a fully open web was always an ideal to aspire to but never something we could fully achieve. Shoot for the stars and all that.

We’re now 30 years into the ad-driven model dominated by Google and the walled gardens of Meta.

This surveillance ad model turned everything into advertising fodder. But it didn’t just sell us products - it shaped public opinion, fueled division, and quietly reprogrammed our attention.

Regulators tried to fix it. In Europe, GDPR placed some constraints on how our data is used, but it also resulted in an endless parade of mostly meaningless cookie consent banners. In the US, protections are nearly non-existent. There you get unbridled exploitation; in Europe you get a little less exploitation and a lot more bother.

And that’s not the worst of it. For all the tools it gave us (I am writing this on Google Docs), Google’s ad-driven platforms turned the web into a barrage of clickbait, conspiracy, and SEO-optimised garbage. Meta learned the lesson that you can make a lot of money that way, social responsibility be damned.

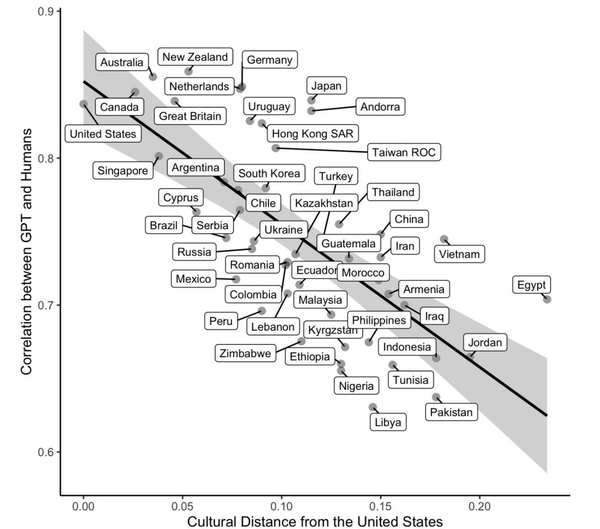

The web was already in dire straits when generative AI burst into the scene, with models trained by scraping everything on the web - books, articles, art - without consent. AI companies sold those models for profit without any compensation or profit sharing with the data owners who made them possible.

Some argue this is “fair use,” that machines “read” the way people do. But I’ve never read more than a book in a day. A few can manage two, and perhaps a rare few can read more. But models that inhale thousands of books in hours or minutes have nothing to do with human “reading.”

Google had already brought publishing to its knees; unlicensed AI training could finish the job. If reporting, writing, and creativity stop being economically viable, how long before the flow of new work dries up, leaving us with nothing but a generic AI generated internet?

We keep trying to patch up the web: GDPR, court cases, Cloudflare’s AI thing .. but at what point do we admit there are too many holes, that the structure itself is failing, and maybe what we need is a reboot?

Do we need to start fresh?

What if we had a second web? A space that preserves the ideals of openness while protecting against their abuse. What might we want from this second web?

- Verified human users: to access it you’d need a login proving you’re human, through a universal identity or login system backed by a neutral body (certainly not the orb).

- Bots and scrapers must declare themselves to websites. Human accounts that behave like bots could be suspended and disabled. Bots that interact with human users must be clearly marked.

- Personal Data Passports: a single interface for users to control what and how their data is shared. See e.g. the Data Box.

- Data Trusts that act for the benefit of large numbers of users, managing how their data is shared and used, including for AI training. See e.g. work by Sylvie De La Crois and Neil Lawrence, The Open Data Institute, and The Ada Lovelace Institute.

- Only privacy-preserving advertising is allowed: see e.g. Kobler’s contextual advertising and Mozilla’s Privacy Preserving Attribution.

- Interoperable social layer: all social applications must use open, interoperable protocols that give users full control over their social graph and content. See e.g. AT Protocol, ActivityPub, and DSNP. Note here that account portability is a must.

- Interoperability and open standards beyond this. Not everything must be interoperable, but key components should be - essentially whatever is required to prevent monopolies and lock-ins.

*There will be things I missed, and I haven’t even touched on the hardware/infrastructure aspects.

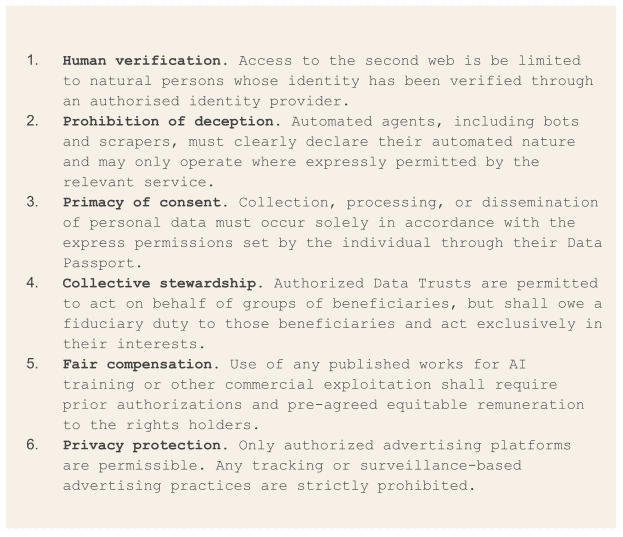

How would these rules be enforced? Through a single, small, clear set of universal terms and conditions. Perhaps one page only, written in plain language, no tricks or ambiguity.

a sketch of what these could look like…

Contracts are a language companies understand. Corporations may resist moral appeals, dodge regulatory scrutiny, and exploit loopholes, but they instinctively recognise and respect binding commercial agreements. When expectations are framed as clear, plain commitments, they not only become enforceable in law but also enter the familiar terrain where businesses operate daily - contracts, liabilities, and obligations. This makes them much harder to ignore or sidestep.

It wouldn’t replace the web we have. The current web would continue, messy and inconsistent as it is. But the second web would be different: a place where humans could participate openly, with rules that actually mean something, and where consent isn’t an afterthought but the foundation of everything that happens.

Using the nature analogy so beautifully articulated by Maria Farrell and Robin Berjon, this would be like an ecological restoration area, protected by strong rules that enable everything within it to thrive. It could start small and grow.

Perhaps the principles nurtured in this second web would spill over into the World Wide Web and steer it back towards its original ideals. In Foundation, this is what happened.

And if the original web is past the point of no return, then at least we’ll have planted the seeds of something new and better.